Schoenberg’s day on Twitter, and a random walk through Kyle Gann’s archive

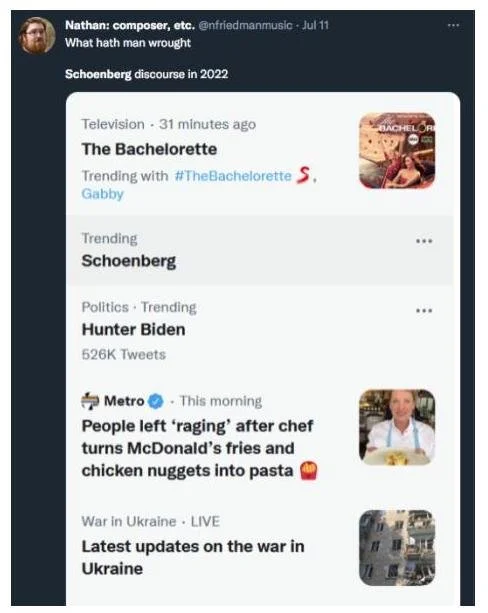

Last week, people who pay attention to the Twitter discourse around whatever “new music” is, or maybe more specifically “Western classical composition,” got a fun blast from the past. I don’t know how it started, but for about 24 hours, starting sometime around Monday, July 11, “Schoenberg” was trending.

tweet by @nfriedmanmusic

From my very perfunctory foray into the conversation, it looked like a few people proclaimed that “Schoenberg killed music” or some other inanity, and folks were taking sides, as one does in any good social media fight. I didn’t get deep enough into the kerfuffle to make any sense of it, but for a second I felt a strange jolt of nostalgia. Through the Twitter fog of self-promotion, political posturing and the range of grievances from petty travel mishap to societal collapse, an actual musical idea briefly had enough ideological valence to provoke a fight. It was refreshing to think that serialism wasn’t just another tool in the grab bag of techniques that composers can choose to use or not use when laboring over a piece that might get one performance before disappearing forever. In our atomised time, when there seems to be so much “new music” being written and so little of it has any staying power or any resonance in the collective conversation beyond a day or two, Schoenberg’s Twitter moment was a flashback to a time when compositional ideas seemed important enough to inspire ideological conflict.

When I started paying attention to “new music” in the late 80’s, composers, musicians, and (to the extent that anyone outside the profession listened to this music) audiences formed Cold War-like blocs. The discourse around composition, as it played out in criticism and in the classroom, was charged with the intensity and the language of geopolitical struggle, even if the battle was over what took place in a few concert venues in Manhattan. In today’s discourse as it happens on Twitter, resigned as it is to “new music” as a marginal pursuit where the best case scenario is a tenure track job and maybe a contribution to a Kanye record, the struggle is not a battle between political blocs for world aesthetic domination, but among individuals carefully protecting whatever patch of territory they are able to stake out. In our apocalyptic era, as it seems like all cultural products, especially ones as plainly elitist as “contemporary classical” music, are being swept away, along with any optimism about the future, maybe it makes sense that we fight for survival, not on behalf of an aesthetic/political creed like serialism. If “new music” as a concept and a practice (and a problematic one - note the scare quotes, which I am about to drop) is under constant existential threat, then we find a spot to build a bunker, maybe find a few allies, and hope for the best. Once upon a time, the struggle was over what new music is, today it’s over whether it exists at all and if so, who gets to make it.

What made this Schoenberg debate especially poignant was that at the moment I became aware of it I was taking a break from perusing the archive of uncollected Village Voice articles Kyle Gann posted a few weeks ago on his website. For anyone who doesn’t know, in addition to being an accomplished composer (check out his recent CD Hyperchromatica for some pleasurably piquant microtonal piano sonorities) and professor at Bard, Gann was the Voice’s main new music critic from 1987 to 2005. More or less weekly, he wrote about the activity of composers and performers in the lofts, clubs, and concert halls of Manhattan, focusing on contemporary music. Another critic, Leighton Kerner, covered more conservative classical music. In 2006, Gann compiled a set of his Voice articles into what might be the most definitive book currently available on Downtown music of this era, Music Downtown. Since that book, and the voluminous archive on Gann’s website, including blog posts, articles, and lectures, represent one of the most expansive records of what happened in certain aspects of the New York music world from the 80’s to the 2000’s, it’s a bit unfortunate that Gann approached his criticism with a pronounced aesthetic/political axe to grind. Gann’s bias was open: he was and is a proponent and practitioner of minimalism and post-minimalism, in the 90’s even ginning up a subgenre he called “totalism” in an attempt to define a certain area of post-minimalist composition (the label hasn’t gotten much traction), and he wasn’t hesitant to imbue his writing with the intensity of geopolitical conflict in defense of that position.

At this point I would like to take a step back and marvel at a few aspects of what I just wrote. One: In the not so distant past, there was so much classical music activity happening in Manhattan that it took two full-time critics to cover it for one weekly paper. Two: that paper, a mainstream, for-profit publication, deemed that particular musical activity newsworthy enough to actually hire those two critics, one of them a working composer and thus hardly impartial, and print their reviews every week. This doesn’t even get into the panoply of other critics who were writing for the Voice at that time, which included music editor Robert Christgau’s role as the purported “dean of American rock and roll criticism” (which always baffled me - I never understood why his taste mattered, beyond his ability to bestow bylines in the Voice), Gary Giddins’s highly influential and idiosyncratic writing about jazz (advocacy from Giddins could be career-making), and the deeply missed Greg Tate (RIP) talking about whatever the hell he wanted. Three: for my younger readers, the idea of a widely-read critic being so openly preferential towards one way of making music might be a foreign concept. They have grown up in an era when mainstream music criticism, to the extent that it exists at all outside of social media and blogs (I’ll admit here that I don’t read Pitchfork so feel free to guide me to writers there who invalidate my argument), mostly feigns a kind of aesthetic naivety, taking the posture of the wide-eyed music lover encountering something for the first time. I’m thinking here of people like New Yorker critics Amanda Petrusich or Alex Ross, both excellent writers who take pains to avoid overtly representing any aesthetic bias. They advocate the basic pleasure of listening to music and discovering the stories behind and around its creation and appreciation rather than representing any particular style or idea. In major publications like The New Yorker or the Times, criticism may or may not still be entangled with the economics and politics of the music business, but if it is, it does it on the down low.

But let me take another big step back. If, having only known it as the clickbaity website it has been for a while now, you’re thinking that the Village Voice didn’t rise to the status of those august media outlets, on a local level, the Voice’s importance in the day-to-day lives of people of a certain socio-economic slice of New York City cannot be overstated. In the waning days of the pre-internet era, which overlapped with my first years in NYC, the Voice had deep influence on the most basic aspects of existence. When I arrived in New York it was not just a newspaper. It was how we found apartments, jobs, places to eat, even how we connected with potential band (and bed) mates. When looking for a new place, it was de rigueur to wait in line at that kiosk in Astor Place for the first copies to get dropped off so we could get an early look at the real estate listings and run to the pay phones to call the landlords. On a wider scale, national distribution meant its cultural reach went well beyond the red plastic box-strewn streets of New York. Even before I arrived there, starting in high school and through college I studied it in libraries to see who was playing in NYC and what the critics were talking about that week. Its critics weren’t just telling people in NYC which gigs they should go to. Their opinions could have tremendous influence over what music broke through into wider cultural awareness, and they knew it.

Even still, from the viewpoint of today’s critical discourse, it’s shocking to see how vehemently Gann used his space in the Voice to practice a kind of musical politics from a clearly defined aesthetic position and to do it in the haughtiest of tones. Even just a cursory random walk through his archive reveals gems like this opening paragraph from what purports to be a review of a December 1986 concert at Phill Niblock’s Experimental Intermedia by improvising vocalist Shelley Hirsch and a November Roulette concert by percussionist/composer Glen Velez, framing the serialism vs. minimalism dichotomy in geopolitical terms:

Music is an analogy for social structure. Serial music harnesses communism's drive for integration, its subjugation of the individual (note) for the glory of the whole (even if the part- less whole usually fails to materialize, either musically or politically). That communist countries condemn serialism is a telling paradox: they prefer to offer the masses an illusion of individuality. Minimalism and its offshoots extract from capitalism the idea of the interchangeability of individuals, with its attendant tolerance for repetition and meaningless variation: the comfort of almost predictability. That universities condemn minimalism is another paradox: academic musicians foster the illusion of their integration into a larger scientific community, which actually couldn't care less about them.

What this has to do with Hirsch or Velez’s music is beyond me (though Velez did work with Steve Reich for years), but Gann’s conflating of the Cold War, the serialism vs minimalism dualism (was there not more happening in new music?) and music’s position in academia, as well as his lofty assessment of his own opinions on music and society, are indicative of both the degree of importance music criticism thought it had in the mid-80’s and Gann’s personal limitations as listener. Gann spends the rest of the review positioning improvisation as a musical “Third World” (his term, and the title of the review), and positioning himself as from somewhere else, where they don’t do such primitive things with music. Improvisation just doesn’t quite conform with what Gann expects to happen in a concert hall. “Critics like myself, with too much training and just enough conscience, often feel as embarrassed at an improv concert as an overdressed tourist.” He spends a few paragraphs on Hirsch and Velez’s music - he likes Velez better, but his distrust in improvisation hobbles his appreciation of both. While he praises Hirsch’s technique (how can he not?), improvisation makes Hirsch sound like “content spread thin.” If only Hirsch had taken the time to look at her work on paper, maybe she could have constructed a more appropriate form. Gann assumes Velez’s work is improvised (hm, why?), but he still likes it better than Hirsch’s because he perceives all of it as being “root”-ed in “ethnic origins.” That allows Velez to build “piece after piece of astonishing sophistication” out of these sturdy materials. The last paragraph starts with a self-aware example of Gann’s racialized understanding of improvised music: “But as much as I prefer the musical results of Velez's traditionalism, I feel uncomfortably like the vacationer who exhorts the Navajo auto mechanic to go back to weaving rugs.” He wants improvisation to be in its own place, separate from his “First World” of the concert hall. A big implication of this review is that Gann wishes the Voice had sent someone other than him to cover these concerts- maybe, given the division of critical labor in the music section, someone who covered jazz, like Gary Giddins or Gene Santoro. Gann was happy to perpetuate the Uptown/Downtown dichotomy that formed the basis of the geopolitics of New York new music at that time, but unfortunately for Gann, Downtown music was more than just one thing. His beat included a slew of musicians who wouldn’t hew to postminimalist orthodoxy, or to the borders between genres, or between composition and improvisation, and therefore didn’t fit his definitions of what “new music” was supposed to be, how it was supposed to be made, or who was qualified to make it. And it bothered him.

Another example of that problem- the first thing I looked at in my random walk was Gann’s review of an October 28, 1987 concert by my dear friend Anthony Coleman at Brecht Forum. Unfortunately, he didn’t like it. Gann speaks highly of some Coleman works that didn’t appear on this concert - his polka for Guy Klucevsek and some other unnamed pieces which “knocked his socks off,” but the actual concert he is reviewing was not up to his standards. Coleman’s playing was “sloppy,” “he’s gonna have to practice.” Gann perceives Coleman’s work as having two sides, improvisation, which he assigns to jazz, not inaccurately in Coleman’s case, and composition, which he assigns to classical. He spends the rest of the review exploring this jazz/classical dualism, saying that it works to improvise on a Monk piece but not on an idea from Xenakis or Ives, because jazz compositions are “solid” and classical pieces are “delicate.” Like Velez’s “ethnic” material, rigorous jazz can stand up to obstreperous improvisers, but sweet innocent classical composition requires gentle care, even something as gnarly as Xenakis. Coleman’s attempt to bring his players’ improvisatory skills into his composition fails because “Wanting to be a club jazzer, Coleman seems determined to let his players follow their instincts; his genius, though, is for crazily individual ideas, for tuning in to wavelengths so weird no regular session man could follow.” Putting aside the absurdity of calling Don Byron and Marc Ribot “regular session men,” Gann’s prescription for Coleman is that, like Gann himself did, he needs to pick a side - dumb his ideas down and compose for improvisors, or get serious and start writing stuff down like a real composer. “My hunch is that he either needs to dilute that genius into a mundane vision his players can contribute to, or else give up the free-and-easy life and write notes on paper.” In-betweenness doesn’t work for Gann. Serialism vs Minimalism is the main compositional dialectic, with improvisation the annoying third wheel taking up space in the musical life of New York. Better to just push it off into the jazz clubs so he can ignore it, but since it’s here in his jurisdiction, the concert hall, he is indignant.

Next I clicked on a review of the 1987 Knitting Factory “Tea and Comprovisation” Festival. You can tell from the name that this is going to bother Gann, and it does. The bulk of the review is a list of the improvisation cliches that annoy him. Thirty five years later, I am sympathetic to the idea that improvised music does have its reliable tropes, which can indeed be boring, but Gann can’t resist the grand dismissal, or the prescriptive pointing towards his idea of compositional rigor through writing things down. On improvising with timbre, Gann again wants people to pick a side, “It is no longer possible to perceive sounds as new in the present technological overload. It's time to quit searching and get choosy, to shift creative effort toward structure and expression.” Or “Spontaneity only arises in a dialectical relation with discipline, a limitation to work against. This is art's primal truth, sublimated in composition, ubiquitously audible in improv.” That audibility is a bad thing? Why not enjoy the sound of players confronting their limitations in real time? The issue is that improvisation is not “disciplined” enough. “Spontaneity” is lazy. It needs to be “sublimated,” or restrained, in a disciplinary, and maybe even carceral, sense, for it to be interesting to Gann. Anyway, I am impressed that Gann is willing to proclaim his knowledge of “art’s primal truth” in the pages of the Village Voice. I wish I had his confidence.

Of course, like Gann, I have my own blatant biases, one of which is that the genre-crossing, sometimes improvised, sometimes jazz-like, sometimes none of those things music that flourished in New York City from the late 70’s to at least the 2000’s and maybe beyond mattered and continues to matter. Another is that one of the most important progenitors of that music, my early mentor Anthony Braxton, is one of the major artists of our time, musical or otherwise. So I had to click on what I think was the first review Gann wrote of something I was involved in, his 1996 tandem review of the first production of one of Braxton’s operas, Trillium R - Shala Fears For The Poor, which we put on at the John Jay College Auditorium, and Mikel Rouse’s opera Dennis Cleveland, produced at the Kitchen. I note now that Gann didn’t even get the complete title of Braxton’s opera right in his review, but nonetheless, without engaging with the content of what Gann says about these two pieces, I also note that Rouse gets twelve paragraphs and Braxton gets four - one paragraph per hour of the opera. Without disputing Gann’s take on something I have no critical distance from, on a purely quantitative level it’s hard not to perceive Gann’s negative review of Braxton as a footnote to his positive one of Rouse. I’m skeptical of the kind of comparison I’m about to do, (and no disrespect to Rouse, whose work I admit I do not know) but I’m confident that over the 25-plus years before these performances, Braxton’s music was drastically more meaningful to more people than Rouse’s, and therefore it might have been reasonable for even a “biased” critic to spend a little more time and space on it relative to Rouse’s than Gann did in this review. Gann concedes that this was “an important premier by an important composer,” but didn’t put in nearly the effort to understand it that he did for Rouse, who happens to be the first composer on Gann’s list in the “totalism” chapter of his 1997 book American Music in the 20th Century (yes, Gann wrote the book on that too). When the serious research on Braxton’s work is complete (I know it is in progress) and Trillium R is studied as a major career turning point for Braxton, Gann’s mini-review is going to look fairly silly.

When this review came out, I complained about it to Mark Stewart, then playing electric guitar in one of Gann’s favorite ensembles, totalism poster children the Bang On A Can All Stars, and also a Braxton collaborator. “They sent Kyle?” he said, and laughed, “Oh, Kyle.” As a frequent traveler across the borders of New York music, from the Fred Frith Guitar Quartet to the pit orchestra of the Showboat revival then on Broadway to Paul Simon’s band, Mark knew all too well that Braxton’s music was outside the map of Gann’s musical world. In a way, like many New York musicians, Mark knew what the Voice editorial office knew - the world of New York music was too complex and too vast for any one critic to cover even a small part of it. Gann’s artistic bias was no secret- he put it right out there, along with his willingness to get on the highest of high horses. His archive, even viewed in this extremely fragmentary way, may be rather skewed, but it’s still a crucial record of a decent chunk of the immeasurably plentiful musical activity of this little corner of the New York music world and the charged language and politics around it. When I go down the list of articles that Gann published in the Voice, collected in Music Downtown and on his website, it’s striking both how huge his body of work is and how incomplete it still is. Besides the music that Gann clearly didn’t appreciate but did write about, there are so many more people whose music didn’t make it into a Voice review, so many musical works that didn’t fit into the critical framework that the Voice built so diligently, so much music that is slipping out of the historical record. Maybe someday someone will undertake a reckoning with that. Or maybe it will drift onto Twitter for a day and disappear again.