Horn Culture

In The Shed With Sonny Rollins

We use the word “work” to refer both to the labor of the artistic process and its result. Music - especially music like jazz that emphasizes improvisation - blurs that distinction. When we hear a master jazz improvisor’s playing unfurl on record or even on stage, it’s tempting to believe that, like when we’re looking at a painting, we are seeing a result, a product, a thing. If we’ve heard enough of his records or seen enough of his gigs, we might think that we know the work of a musician, even one as great as Sonny Rollins. In that version of knowledge, based on hearing the public performances, what it took for him to get there, work in the sense of labor, is something else: the private practice and research that prepares for the golden moments of execution that the audience experiences.

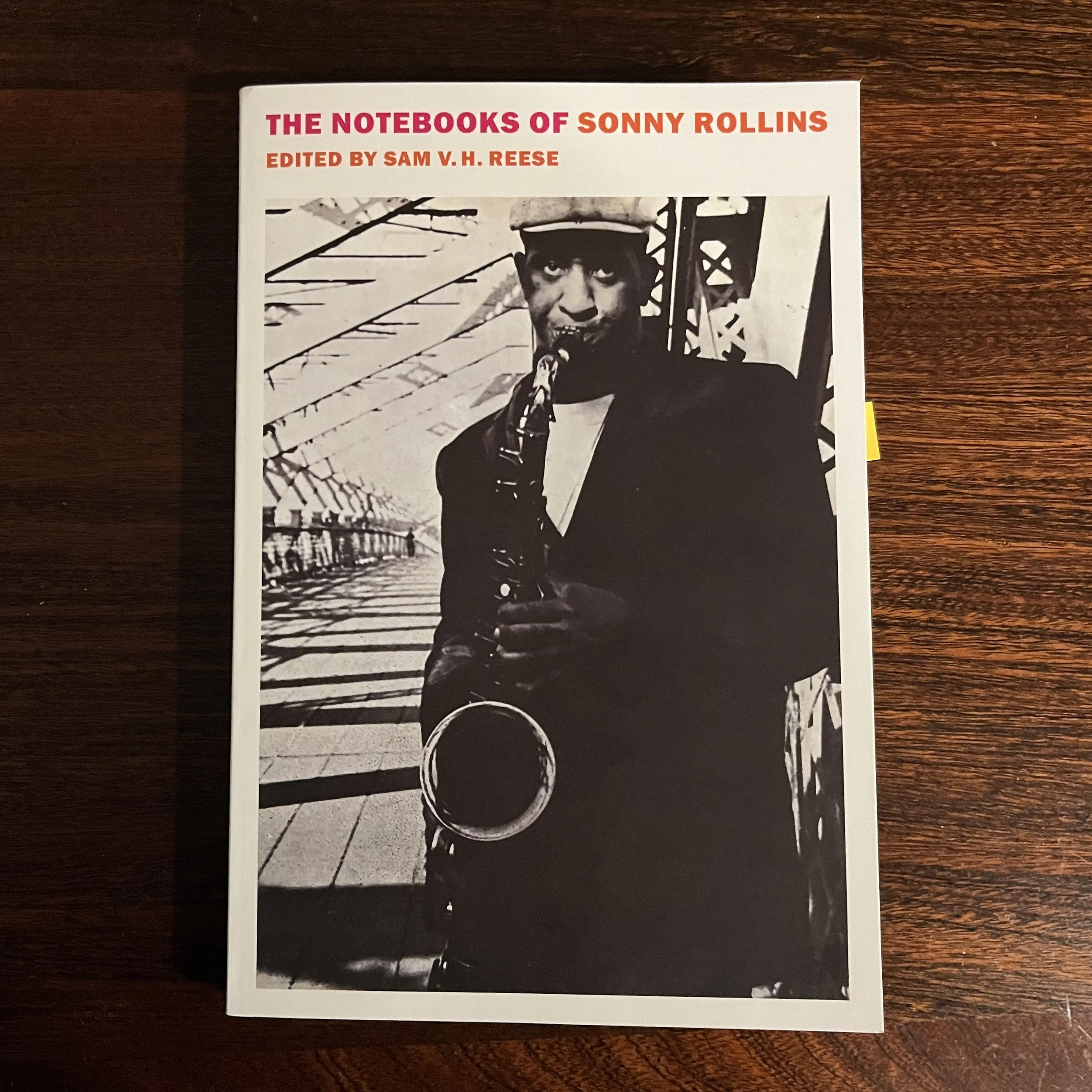

The practice room or the rehearsal studio is off limits to the audience, a private space of discipline and discovery(1), known, at least since the heroic, mythical moment when Charlie Parker took a saxophone and a stack of Count Basie 78’s to a cabin in the Ozarks and transformed himself into the architect of the bebop revolution, as “the woodshed” - “to shed” in its verb form. We are told Parker memorized a bunch of Lester Young solos by slowing down the records(2), an early example of how recording technology and jazz’s evolution are intertwined on the pedagogical level as well as artistically and commercially, but we don’t really know what went on in that shed. Lucky for us, this is not the case for Sonny Rollins. When he was in the shed, he took notes. Some of them are available in the new book The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins, edited, with deep respect for Rollins’s technical geekery, humor, candor, and poetic non-linearity, by Sam V.H. Reese.

The Rollins persona, both in its public manifestation on stage and its mythical dimension of story and legend - the physically imposing, mohawk-sporting, musically domineering trickster of the tenor saxophone, his tone so huge, his rhythmic feel so mercurial and his harmonic control/freedom so complete that for a time it left no space for sidepeople other than bassists and drummers; his own Parker-esque mythical woodshed moment absenting himself from the scene so he could make hermetic discoveries on the Williamsburg Bridge (gloriously depicted in this quilt by Faith Ringgold that appeared recently on the cover of the New Yorker); his dogged individuality existing both at the heart of jazz’s mainstream and at the same time outside the rigid categorization of the manifold aesthetic subcategories that emerged over his long career like hard bop, free jazz and fusion - crowds out the idea of Rollins as worker. Rollins’s status as character, and even as symbol of the tenor saxophone or “modern jazz” itself, might suggest that Rollins emerged fully formed, a prodigy who didn’t need to futz around with the same tedious exercises that the rest of us do when we practice our instruments. After all, Rollins was the “Saxophone Colossus,” as his album title said - suggesting a giant classical statue astride the gates of the great river of jazz. It would be nice to imagine that on his own in the practice room Rollins was thinking about metaphysical matters, like a character in Nathaniel Mackey’s epic From a Broken Bottle series of epistolary novels about mystical music-making. And some of the time, he was. But in this book, more often than not, Rollins thinks about more basic, tangible or embodied things like intervals, hearing the overtone series in individual pitches, and how to accent particular notes in scales. He thinks about his teeth, his tongue, how smoking affected his breathing, and where exactly to put his pinky finger on the saxophone key.

The saxophone is the book’s love interest and its antagonist, a physical object imbued with libidinal power that both attracts and resists Rollins. In 1961, presumably as an introductory note to a saxophone method book he never finished, he wrote about seeing it for the first time in the window of Manny’s, the legendary now-defunct music store on West 48th St., near Times Square,

Boy I wish I had one of those… and could play it too!...

That’s how ‘Sax Men’ begin. From the first time they lay eyes on that curved shiny beautiful-looking piece of metal, it makes them feel proud and strong and important. Yes, important! If you had that sax you would really be somebody important. You would make people dance and be happy.

Yes, you can see yourself now, standing in front of those people and filling them with tones straight from your sax, handsomely groomed and dressed, horn gleaming like the sun as you perform in front of the crowds.

Rollins was right. In his hands the saxophone did make him important, it did make people dance and be happy. In order to do that, as we see in this book, Rollins had to go through a continual process of aligning his body and mind in order to overcome the instrument’s inconsistencies, limitations, and idiosyncrasies, to get closer to the abstract possibilities he perceived in the basic stuff of music - individual pitches, intervals, harmony. He is constantly suggesting different ways to position his lips, tongue and teeth. For the first three of the book’s four sections, he struggles with reeds, mouthpieces, and even different instruments, alluding to Bueschers and Selmers, searching for the horn that will get him closer to the sound he imagines. Rollins is locked in a love triangle with the saxophone and the raw materials of music, constantly discovering the gestures that he has to make with his body to get the other two points on the triangle to align. Rollins’s playing, especially on his early records through the mid-60’s, sounds so effortless that it’s hard to believe it took so much frustration and work to achieve, and yet every musician has experienced that drive towards these objects that won’t do anything without our skill and imagination animating them.

I’d imagine for saxophone players there is a wealth of technical information here - but for someone like me who has been saxophone-adjacent for most of my life but whose interest in the horn is that of an outsider, technical notes like this one suggest the universes of thought and work that go into the simple articulation of a couple of notes on the intricately monomaniacal instrument: “On going down from low C B Bb, minimize the left pinky stretch to the brass-most part of the key in favor of the new concept of a more straight-down from B to Bb manipulation. This straight up and down fingering is best exemplified when ascending from Bb to B etc. on upward.” I don’t know exactly what that means or feels like, but it illustrates the attention to physical detail it takes to play with the complexity of phrasing Rollins achieved, and does it with a poetic suggestion of the directionality of musical lines in its own phrasing - especially if you read it in the almost Kermit the Frog-like voice he has had for the last few decades. I recommend having that voice in your ear as much as possible when reading this book. Nonetheless, Rollins’s struggle to get his pinky finger to do what he wants it to do is as human as it gets. This is a big part of what we will lose as digital technology encompasses more and more musical activity, standing as we are on the threshold of the era of AI-generated music.(3)

It is to Reese’s editorial credit that he included so much shop talk, but Rollins writes in several different modes or registers: notes to self on matters ranging from the saxophone to bandleading to diet, digestion, drugs, politics and spirituality; more formal writing on the saxophone that seem to be notes for his method book; drafts of work-oriented documents like correspondence with friends and dignitaries. The ratio of those modes shifts over the course of the four chronological sections. In the first chapter, spanning 1959-1961, the so-called “Bridge Years” when he took his first extended break from public performance, quick notes on his daily practice predominate, the kind of thing any instrumental teacher would recommend a student to do, like this note on phrasing, “On all melodies, after playing a phrase and reaching for a breath, always start the next phrase more softly then build up volume through succeeding phrasing, especially on ‘ballad/bottom of the horn’-type melodies.” To see that idea clearly articulated, from a player whose majestically idiosyncratic and complex approaches to phrasing deserve a book of their own, is stupefying. Is it really that simple?

In the second section from 1961-1963, we see drafts for his method book start to take over, and with it a tone of exaggerated formality that borders on kid-friendly poetry, as in this revision of his earlier introductory note, now charged with a different register of psychoanalytic richness:

The saxophone is our friend.

He wants to make us happy. He wants to serve us. I’m glad that he’s our friend (or that he likes me), because from the first moment I saw the saxophone I fell in love with it, and wanted so badly to have one and play one. The saxophone has taught me so much since the first time I laid eyes on it and it has served me well. Many times I made myself unhappy and the saxophone made me happy again. Many times I made my body sick and the saxophone made me all better again. Many, many times and forever and ever it will be so (it has promised to do so).

The desire and hope in that paragraph, not just that “music is the healing force of the universe” as Albert Ayler said, but that this object, the saxophone, contains so much libidinal agency that it can cure the player in a real way, is both a truth and a lie. Rollins - as his constant comments on health bear out - knows that the horn by itself doesn’t do anything and may even be destructive to his own body in terms of his dental issues and his struggles with substances that may or may not fuel his musical inspiration. What heals, and what teaches, is the depth of Rollins’s dedication to the horn and the discoveries he makes through it in the course of his daily practice.

Rollins’s focus expands in the third section. We still see technical and health notes, but business concerns arise as do comments on jazz as a style and a lineage as well as broader spiritual/psychological/sociological/philosophical takes on music and his relationship to it. Some of these are strikingly self-aware:

More music please.

I am a singular artist.

I do a singular thing.

In that short almost-poem Rollins precisely defines his unique crystallization of the potential of jazz - and maybe music itself - into being a “singular artist.” We see that in this frustrated note to his sidemen: “It happens all the time, I know- but it’s not going to happen to me. You guys have forgotten that you are here to play for me. You’re supposed to be playing for me. Accompanying me! Helping me to do something.” Though the wide range of approaches he took with different bands show the depth of his listening to his bandmates, he was not a collaborator like Duke Ellington, someone whose genius spiraled outward to encompass a range of other musicians’ genius - from all of the legions of brilliant members of his orchestra to his great writing partner Billy Strayhorn; or even a bandleader like John Coltrane, who was one of Rollins’s few instrumental peers, but whose artistry is inseparable from the way it formed a long-term feedback loop with the other members of his great quartet. Though Rollins did lead bands and compose, in this book it appears that most if not all of Rollins's genius and artistry went into mastering a certain way of playing the saxophone. That was his job. It wasn’t promoting himself or running a business (he had someone else to do those things, as we will discuss later) or producing records, or really even composing, all things today’s jazz musicians are expected to do.

In the final chapter, the ratio of sax talk to other concerns flips. The world outside the practice room looms large, in the form of drafts of letters to politicians, deep thoughts on the state of the world, and even some business minutiae, like a heart-breaking draft of a bio, which any working artist or writer or musician, will recognize even if we can’t claim as exalted a status. I shuddered at the image of Rollins having to write “For the past 40 years Sonny Rollins has been making and remaking Jazz history, day by day… There is the feeling that the truly great artists are gone - Parker, Ellington, Armstrong, Holiday, Tatum, Miles, Coltrane. Rollins is the last remaining Titan,” a sentence that contains within it both the auto-puffery of DIY public relations writing and the pain of living through the end of a golden era. That sentence, including a short list of jazz legends who were Rollins’s contemporaries and in some cases colleagues, hints at the deep lacunae encoded in the blank spaces between the mostly short jottings that form Rollins’s notebooks as shaped by Reese.

One of the most fascinating (to me) near-absences is talk about records. Not only does he almost never discuss making or even listening to recordings - not to mention having opinions on them - I couldn’t help but notice that Rollins’s woodshed, unlike Parker’s, did not seem to have a record player in it. The kind of ear-based, transcription-oriented learning commonplace in jazz pedagogy at least since the bebop era was not part of Rollins’s practice as depicted here. But not only that- to the extent that records became the basis of both jazz’s real-time reception by global audiences and the bedrock on which its canon was built, it’s a powerful reminder that Rollins didn’t experience jazz filtered through the palimpsest most of us know through its representation on recordings. As he says in his bio draft, he lived jazz history “day by day.” That this book provides an intimate look at what made up that daily life, its almost total lack of music business filtering and mythologizing (made all the more clear by its presence when we do see it), makes it an essential reminder that people like the ones Rollins listed in his bio were real human beings not gods, and they had to think about things about quitting smoking, whether to replace their bass player, and if their diet might be causing digestive strain bad enough to cause an on-stage “accidental elimination.”

Late in the book, the earlier phrase “Many, many times and forever and ever it will be so (it has promised to do so),” takes on a sad naivety. After his wife Lucille dies he writes,

“Things have been quite strange here for me even though Lucille had psychologically prepared me for this inevitability. We had been married for 50 years after all.

I have recently decided to start back performing (for a while I didn’t have any incentive to practice or contemplate a future!) and that is why I momentarily assumed a resumption of the travel arrangements which were so impeccably handled by Lucille.

Sonny--

Maybe think about retirement when listening to my playing (technically) at this point).”

It’s hard to tell from the page break if those are one or two entries but they feel linked. In the first two sentences we see both the inevitable and deeply sad realization that the saxophone will not save him “forever,” and a rare look behind the curtain at the essential role Lucille played in managing the practicalities that enabled him to achieve his singularity. As is so often the case, the singularity masks a duet - there is a woman laboring in the background, uncredited. The “Sonny--” is not Rollins talking to himself, it’s an echo of Lucille’s voice breaking him the bad news that his long career is winding down, in the same way that he quoted her in the title of his last studio album, “Sonny, Please.”

In the decade since Rollins made the decision to retire, a rare accomplishment for jazz musicians in its own right, he has existed as a kind of supreme elder guru in sacred seclusion somewhere upstate, occasionally bestowing us with messages like this New York Times Op-ed that hinted at the kind of thought and articulation behind the Rollins myth that this book so poetically expands. Even as the world that he emerged from seems to disappear ever deeper into a historical realm of legend, his singularity persists. He serves art as a reminder of higher zones of achievement outside the “cruel accounting,” to use a phrase of Fred Moten’s(4), of today’s neoliberal world. Speaking of travel arrangements, I once heard a story about Rollins, possibly an urban legend. Another saxophonist - in the version I heard it was Joe Lovano - was in the first class boarding line at JFK airport for a flight for London when he saw Sonny Rollins. He asked Rollins why he wasn’t in first class and Rollins responded, “Oh, Joe. I’m in Royal Class.” It’s no surprise to anyone who knows Rollins’s work that he would have access to a higher level beyond first class, known only by a few. That Rollins and Reese provided this glimpse into the thinking and labor that got him there is a surprise gift to anyone who loves Rollins’s music - and anyone involved in a creative practice.

***

notes:

I have to credit this 2021 zoom talk, “On Fugitive Aesthetics,” with Fred Moten, Stefano Harney and Michael Sawyer, for helping me think through the tension of this public/private distinction, especially the long section in which they discuss NBA star Allen Iverson’s notorious “practice” press conference.

I first heard this story in Ross Russell’s pulpy 1973 Parker biography Bird Lives.

Here I am deeply indebted to Non-Things, Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han’s 2022 book on the ramifications of humanity’s transition towards digital life.

Also from the zoom talk linked above. Moten says this towards the end of a long paraphrase of Iverson.